Special Mosquitoes Being Bred to Fight Dengue

In Honduras, dengue fever prevention has meant teaching people to avoid mosquito bites and fear them for decades. Presently, Hondurans are being instructed about a possibly more successful method for controlling the sickness — and it conflicts with all that they've learned.

This makes sense of why twelve individuals cheered last month as Tegucigalpa inhabitant Hector Enriquez held a glass container loaded up with mosquitoes over his head, and afterward liberated the humming bugs very high.

Enriquez, a 52-year-old bricklayer, had elected to assist with publicizing an arrangement to smother dengue by delivering a huge number of extraordinary mosquitoes in the Honduran capital.

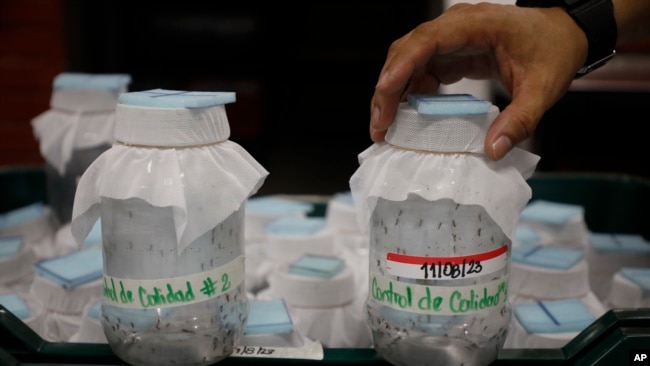

Scientists bred the mosquitoes that Enriquez released in his dengue-endemic neighborhood of El Manchen to carry the bacteria Wolbachia, which prevents the disease from spreading. These mosquitoes spread the bacteria to their offspring when they reproduce, reducing the likelihood of future outbreaks.

This arising methodology for fighting dengue was spearheaded throughout the past 10 years by the philanthropic World Mosquito Program, and it is being tried in excess of twelve nations.

With the greater part of the total populace in danger of contracting dengue, the World Wellbeing Association is giving close consideration to the mosquito discharges in Honduras, and somewhere else, and it is ready to universally advance the technique.

In Honduras, where 10,000 individuals are known to be nauseated by dengue every year, Specialists Without Lines is joining forces with the mosquito program over the course of the following half year to deliver nearly 9 million mosquitoes conveying the Wolbachia microscopic organisms.

"There is an urgent requirement for new methodologies," said Scott O'Neill, pioneer behind the mosquito program.

Dengue challenges run-of-the-mill anticipation

Researchers have taken extraordinary steps in ongoing a long time in diminish the danger of mosquito-borne sicknesses, including jungle fever. In any case, dengue is the exemption: Its pace of disease continues onward.

Models gauge that around 400 million individuals across about 130 nations are tainted every year with dengue. Death rates from dengue are low - an expected 40,000 individuals bite the dust every year from it - however flare-ups can overpower wellbeing frameworks and power many individuals to miss work or school.

"At the point when you catch an instance of dengue fever, it's frequently likened to getting the most pessimistic scenario of flu you can envision," said Conor McMeniman, a mosquito scientist at Johns Hopkins College. It's ordinarily known as "breakbone fever" for an explanation, McMeniman said.

Customary techniques for forestalling mosquito-borne diseases haven't been close to as powerful against dengue.

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that most usually spread dengue have been impervious to bug sprays, which have passing outcomes even in the most ideal situation. Furthermore, on the grounds that dengue infection comes in four unique structures, controlling it through vaccines is more earnestly.

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are likewise a difficult enemy since they are generally dynamic during the day - implying that is the point at which they chomp - so bed nets aren't a lot of help against them. It is anticipated that climate change and urbanization will make the fight against dengue even more difficult because these mosquitoes thrive in warm, moist environments and dense urban areas.

"We really want better instruments," said Raman Velayudhan, a specialist from the WHO's Worldwide Disregarded Tropical Infections Program. " Wolbachia is certainly a long haul, reasonable arrangement."

Velayudhan and different specialists from the WHO intend to distribute a suggestion as soon as this month to advance further testing of the Wolbachia methodology in different regions of the planet.

Researchers amazed by microorganisms

The Wolbachia procedure has been a very long time really taking shape.

The microorganisms exist normally in around 60% of bug species, only not in the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

"We worked for a really long time on this," said O'Neill, 61, who with assistance from his understudies in Australia in the end sorted out some way to move the microbes from natural product flies into Aedes aegypti mosquito undeveloped organisms by utilizing minute glass needles.

Close to quite a while back, researchers meant to involve Wolbachia another way: to reduce the number of mosquitoes. Scientists would release infected male mosquitoes into the wild to breed with uninfected females, whose eggs would not hatch because male mosquitoes carrying the bacteria only produce offspring with females who also have the bacteria.

In any case, en route, O'Neill's group made an amazing disclosure: Mosquitoes conveying Wolbachia didn't spread dengue — or other related illnesses, including yellow fever, Zika, and chikungunya.

What's more, since contaminated females pass Wolbachia to their posterity, they will ultimately "supplant" a nearby mosquito populace with one that conveys the infection-impeding microbes.

The substitution system has required a significant change in contemplating mosquito control, said Oliver Brady, a disease transmission expert at the London School of Cleanliness and Tropical Medication.

"All that in the past has been tied in with killing mosquitoes, or in any event, keeping mosquitoes from gnawing people," Brady said.

The World Mosquito Program has conducted trials affecting 11 million people in 14 countries, including Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Fiji, and Vietnam, since O'Neill's lab first tested the replacement strategy in Australia in 2011.

The outcomes are promising. In 2019, a huge scope field preliminary in Indonesia showed a 76% drop in detailed dengue cases after Wolbachia-contaminated mosquitoes were delivered.

In any case, questions stay about whether the substitution system will be compelling - and financially savvy - on a worldwide scale, O'Neill said. The three-year Tegucigalpa trial will cost $900,000, or about $10 for each person Doctors Without Borders hopes to protect.

Researchers aren't yet certain the way that Wolbachia really obstructs viral transmission. Furthermore, it isn't certain if the microorganisms will function admirably against all types of the infection, or on the other hand in the event that a few strains could become safe over the long haul, said Bobby Reiner, a mosquito specialist at the College of Washington.

"It's positively not a limited-time offer fix, everlastingly ensured," Reiner said.

0 Comments